Of the many species of lilies, Lilium candidum, commonly called the Madonna lily, has by far the most symbolic importance. The plant originated in what is now Israel, Palestine and Lebanon and spread over the whole Eastern Mediterranean. Despite being rare in the wild, in its native dry rocky habitat, it has come to thrive at lower altitudes and is a favourite in decorative gardens.

With their leafy floral stems that shoot up over a metre in height and their sweetly fragrant white flowers, they have become a symbol for beauty and purity across disparate cultures. Depictions of lilies are found on Assyrian carvings and Egyptian tombs, they were said to decorate the columns of King Solomon’s temple where their six petals had symbolism with the Star of David, and in Greek and Roman times they were used for the ritual bridal wreath at marriage ceremonies. The beauty and purity of Lilium candidum was taken up by medieval artists and became a symbol for the Virgin Mary, which is how it gets it common name as the Madonna lily. The Madonna lily still features heavily in art and has a special link to Magdalen College and our coat of arms.

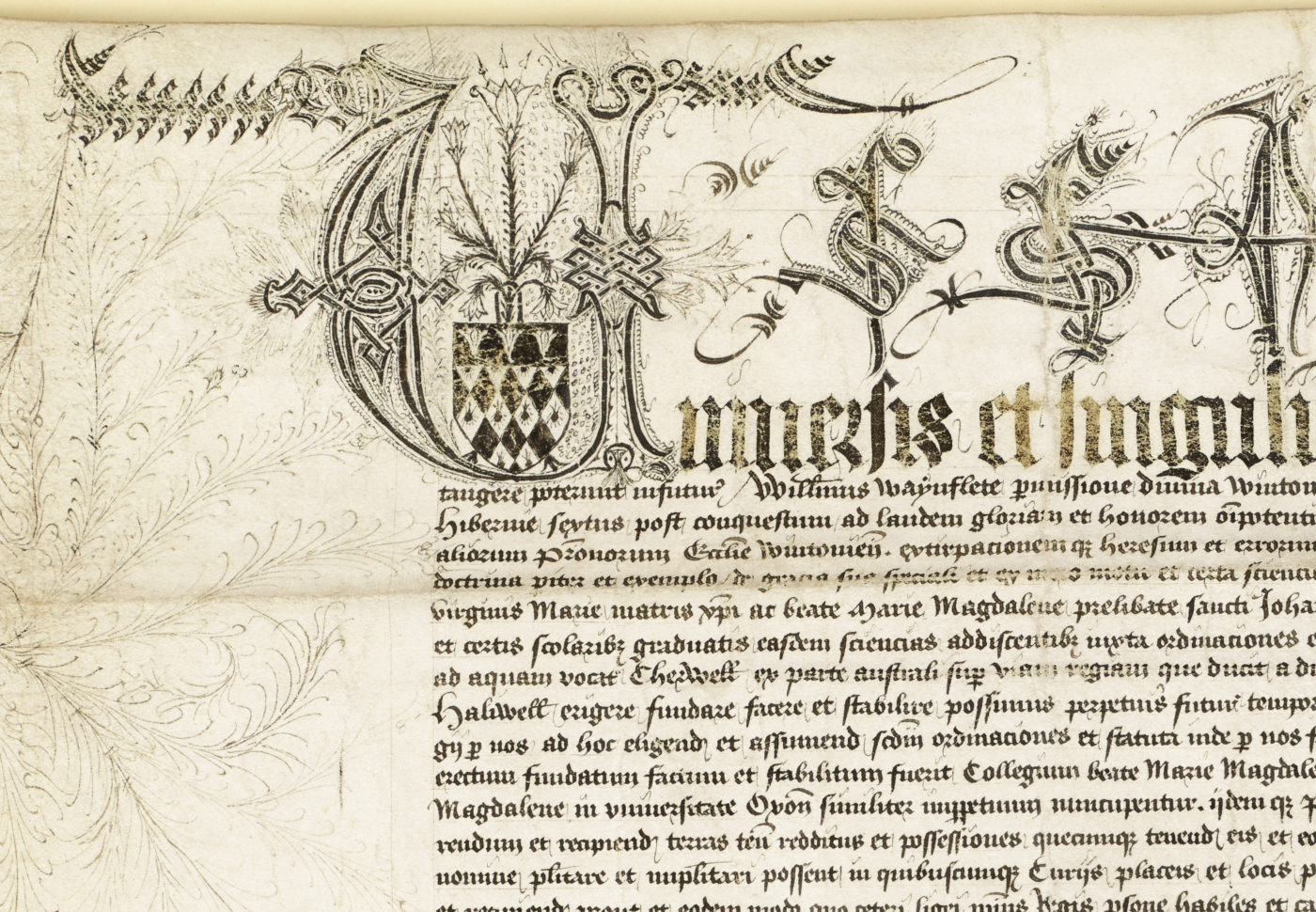

The lilies which adorn Magdalen’s coat of arms are a direct links to the founder of the College, William Waynflete, Bishop of Winchester and Lord Chancellor of England. It was from Waynflete’s own coat of arms that the lily was taken up as the emblem of the College upon its foundation, as seen at the head of our foundation charter from 1458. What makes Waynflete’s own coat of arms interesting is that it was not the same that he was born under.

Instead, Waynflete changed his coat of arms during his own lifetime. William Waynflete was born William Patten in Wainfleet (Lincolnshire), son of Richard Patten (alias Barbour) a merchant. The arms of the family of Patten have been described as a “field fusily ermine and sable”. This means that the background of the shield, known as the field, consisted of a diamond shaped pattern. The term “fusily” or “lozengy” refers to the rhombus shape which form the backgrounds. “Ermine” and “sable” refers to the patterns which fill the diamonds, both descriptions making references to animals – ermine refers to the winter fur of a stoat which have white fur and a black-tipped tail. The diamond shapes filled by the ermine pattern is an attempt to represent the ermine fur as it would be found on royal garments and can be seen on the coat of arms as a white background with a stylised black tail with three studs at the top. The remainder of the diamonds are filled with black, referred to as “sable” after the black fur of a sable.

William Patten chose to change his coat of arms when he became William Waynflete. To his father’s Patten arms he added on a “chief”, or banner above, “three lilies slipped argent”. “Slipped” refers to the lilies being displayed with a stalk and not just as an isolated flower and “argent” derives from the Latin argentum for silver, although silver is often displayed as white in coats of arms. Thus arriving at the familiar coat of arms of Magdalen College.

But why did William Waynflete decided to add these lilies to his father’s coat of arms? The answer lies in his time before founding the College, when he was an educator both as Master of Winchester College and then more crucially as Provost at the newly formed King’s College of the Blessed Mary of Eton by Windsor – more commonly known in its abbreviated form, Eton College. The coat of arms of Eton College granted by King Henry VI also has three Madonna lilies. It is believed that it is from these lilies that Waynflete was inspired to add the flowers to his own coat of arms as both a token of gratitude to the King and in his role as an educator, as the three lilies were gifted to Eton by the King to symbolise “the brightest flowers redolent of every kind of knowledge”. Whatever the reason was that Waynflete adopted the lilies they have become an icon of the Magdalen College and have been reproduced on a plethora of objects from the rowing blades of the Magdalen College Boat Club to wallpaper.

But why did William Waynflete decided to add these lilies to his father’s coat of arms? The answer lies in his time before founding the College, when he was an educator both as Master of Winchester College and then more crucially as Provost at the newly formed King’s College of the Blessed Mary of Eton by Windsor – more commonly known in its abbreviated form, Eton College. The coat of arms of Eton College granted by King Henry VI also has three Madonna lilies. It is believed that it is from these lilies that Waynflete was inspired to add the flowers to his own coat of arms as both a token of gratitude to the King and in his role as an educator, as the three lilies were gifted to Eton by the King to symbolise “the brightest flowers redolent of every kind of knowledge”. Whatever the reason was that Waynflete adopted the lilies they have become an icon of the Magdalen College and have been reproduced on a plethora of objects from the rowing blades of the Magdalen College Boat Club to wallpaper.

Lilies were adopted by Colleges earliest architects and stonemasons as a central theme to decorate Waynflete’s new edification. Lilies continued to be use by the great reformers of College’s buildings and can now be found in the most obvious and most unexpecting places.

Brocaded silk orphrey panel, c. 1500

This orphrey panel, probably taken from Bishop Waynflete’s ecclesiastical robes, is woven with small gold thread pomegranates within ivory strapwork and foliage, restored; appliquéd onto modern ivory silk, mounted on each side with late 15th early 16th century lily sprays of floss silk couched with gold. These now hang in the President’s Lodgings and are some of the finest preserved examples of 15th century English embroidery.

Decorative wallpaper designed by A.W. Pugin (1850)

A.W. Pugin was a leading 19th century architect, famous for his role in the Gothic Revival style of architecture and for his work on the Palace of Westminster in London and the Elizabeth Tower which houses Big Ben. He was a great enthusiast of Magdalen College and drew many sketches of the architecture here while training under his father. He was employed to design a new main gateway into the College in the 19th century which was erected in the 1840s but unfortunately only stood for 40 years before it was removed when plans were made to design St Swithun’s Quadrangle. However, one item of Pugin’s craftsmanship still remains in the College, the above intricate wallpaper that decorates the formal dining room in the President’s Lodgings. The wallpaper, made by woodblock print, features both the coat of arms and Madonna lilies and was designed in 1850 when Pugin was working on the furnishings and the magnificent wallpapers of the Houses of Parliament. It is presumed that the wallpaper was designed for Pugin’s good friend, John Bloxham (longtime Fellow of Magdalen), but never realised. The original blocks were rediscovered in the mid-1990s and were used to print the wallpaper which now adorns the formal dining room (as well as a roll which was donated to the Victoria & Albert Museum). The Waynflete arms and the form in which they were used in that time are central to the motif, as is the elaborate double-W for Waynflete. You can see the rose on rose, York on Lancaster. Pugin’s motif of the sprig of lilies is the version of the sprig of lilies appears in the single piece of fifteenth-century orphrey panel (above) from the cope of William of Waynflete.

A writing slope designed by James Wyatt in 1792

The “Chancellor’s Chair” designed and carved by James Wyatt, 1792. Preserved in the President’s Lodgings, Magdalen College.

This writing slope, or escritoire, was carved from part of the “celebrated large oak mentioned by the Founder” and carved at the same time as the Chancellor’s Chair at Magdalen College (now in the President’s Lodgings, right) in 1792 by James Wyatt. After a 15 year apprenticeship, Wyatt set up with business as a carver and gilder at 115 High Street in 1805. He began dealing in pictures and prints in 1811 and his shop became a favourite haunt of Pre-Raphaelites, such as Sir John Everett Millais. Wyatt was elected Sheriff of Oxford for 1839-40 and Mayor of Oxford for 1842-43.

Artist and botanist Dr Chris Thorogood worked with academics from Magdalen College, and art historians from the Ashmolean, to produce a modern, Pre-Raphaelite-inspired oil painting that highlights the important linkages among art, observational drawing, and scientific accuracy. “The Lily Garden” displays the important linkages among art, observational drawing, scientific accuracy and interpretation using the Madonna lily as a model: an icon of art through the ages, and an important part of Magdalen College’s natural history.

This is a Pre-Raphaelite-inspired botanical illustration, commissioned for the 2018 exhibition, The Flora & Fauna of Magdalen College. Madonna lilies are an important component of Magdalen College’s natural history. The botanical interpretation of the Madonna lilies in the current painting is Pre-Raphaelite-inspired for two reasons: firstly because the plant is such an important symbol in the Brotherhood’s work in the 19th century; secondly, the Pre-Raphaelites depicted objects from nature scientifically, carefully studying them from nature. This has striking similarities to the art of botanical illustration – a discipline grounded in close observation, detail and accuracy to generate aesthetically pleasing and scientifically important art. The Mediterranean backdrop depicts the habitat in which the Madonna lily evolved and still occurs locally to this day. It is also vaguely reminiscent of the Classical antiquity of Alma-Tadema’s 19th century paintings, which famously depict scenes of the luxury and decadence of the Roman Empire in a Mediterranean setting.

“I have always been inspired by the Pre-Raphaelites’ paintings,” says Dr Thorogood, “When I was a child I remember gazing up at them in the galleries in London. The Lily Garden is borne from a fusion of my life-long passion for the Brotherhood’s art, from my own experience as an artist, and from my field observations as a botanist in the Levant and the Mediterranean.”

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in 1848. They revived an archaic style to achieve a particular effect in their paintings, including the use of symbols that referred to the Virgin. The Pre-Raphaelite depicted objects from nature scientifically, carefully studying them from nature. Indeed, plants were depicted with a striking life-like quality more reminiscent of the 19th century – an era of photography, and empirical botanical science. Thus the Madonna lily, rather than a stylised symbol, was depicted with remarkable fidelity, depicting the floral structures of tepals and stamens with botanical accuracy and detail. The accuracy with which these artists depicted plants is reminiscent of scientific botanical illustration, and an interesting juxtaposition between art, scientific accuracy and symbolism of plants.

invitation issued to Robert Gunther, a young science Demy at Magdalen who would later become a Fellow. Magdalen College P309/X2/2

“May Morning on Magdalen Tower”by William Holman Hunt, one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, is a prime example of scientific detail being deployed in dramatic portraiture – the centrepiece of the painting is a choir boy holding a Madonna lily. The Pre-Raphaelites were famous for their accuracy at depicting botanical objects. This painting is no exception, with the lily representing both a symbol of purity but also drawn accurately in a style more reminiscent of botanical illustration. Hunt took the trouble to include a number of well-known Magdalen faces in the painting including: the Professor of Physiology, John Burdon Sanderson (Fellow 1882–94), the Professor of Music, Sir John Stainer (Organist 1860–72), the theologian Henry Bramley (Fellow 1857–1905), John Bloxam (Fellow 1835–62), and Herbert Warren (President 1885–1928). Hunt kept a regular correspondence with a number of Magdalen officers during the creation of his work, including Organist John Varley Roberts and then Senior Demy R.T. Gunther (later Fellow).

Madonna lilies are also an important part of Oxford University’s history, and feature prominently in the Pre-Raphaelite-inspired artist Charles Allston Collins’s painting “Convent Thoughts”, which hangs in the Ashmolean. The flowers were painted in the Oxford garden of Thomas Combe, an early collector of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, and the model was his housemaid, Frances Sarah Ludlow. Combe bought the painting and in 1894 he bequeathed his art collection to the Ashmolean Museum. Lilies also feature in the frame which was designed by Collins.

Alongside their decorative role, lilies were also the focus of botanical research carried out by a member of the College, Robin Snow. George Robert Sabine Snow, ‘Robin Snow’ (1897-1969) was an undergraduate in Oxford and studied under the then Sherardian Professor of Botany Frederick Keeble (Fellow of Magdalen College) in the Botany Department. Snow then took up a Fellowship by Special Election at Magdalen College in 1922 which he continued until his retirement in 1960. During his time in Magdalen he also was the first to take up the post of Garden Master.

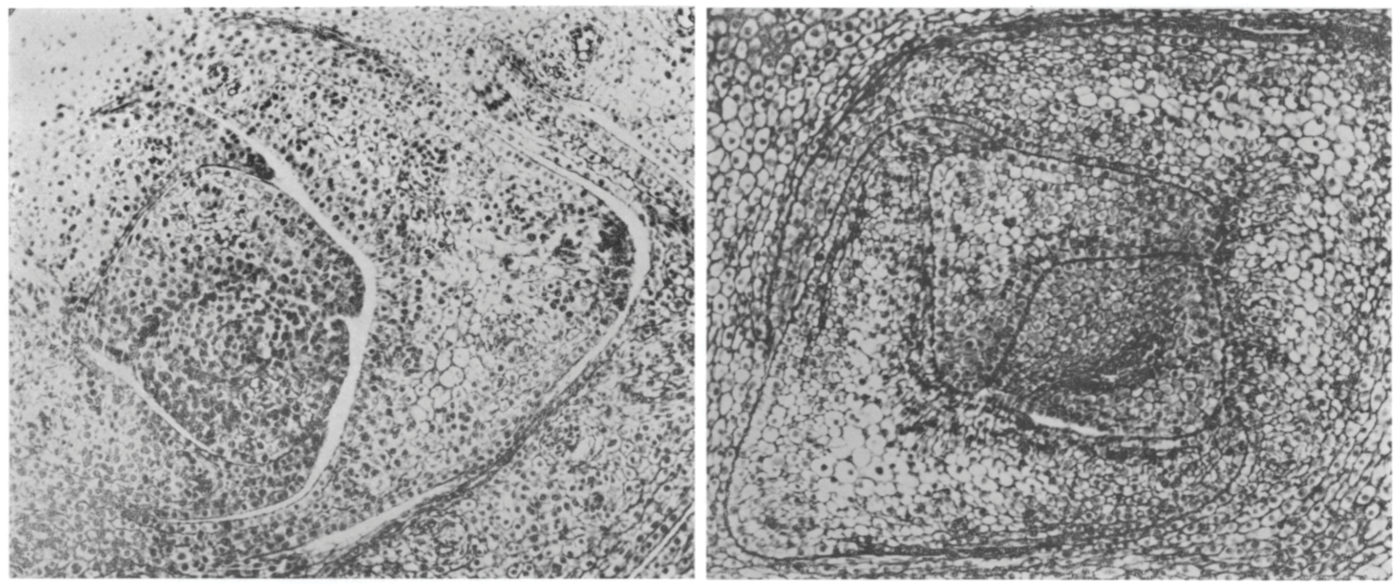

In 1930 he married Christine Mary Pilkington, also a botany student at the University. Together the Snow’s carried out a number of ground breaking experiments on the growth and development of plants. They are most famous for their work on the development and arrangement of leaves known as “phyllotaxis”. By performing minute surgical experiments (carried out by Mary with a ‘cataract knife’ under a microscope) on the growing points of shoots they were able to show that the phyllotaxis of leaves could be experimentally modified. They identified that the position of new leaves is influenced by the sites of pre-existing leaves. This work was part of the foundation of the now widely accepted hypothesis that pre-existing leaves dictate the position of new leaves through the generation of inhibitory fields. The Plant Sciences Department in Oxford still hosts a “Mary Snow lecture” in honour of their work.

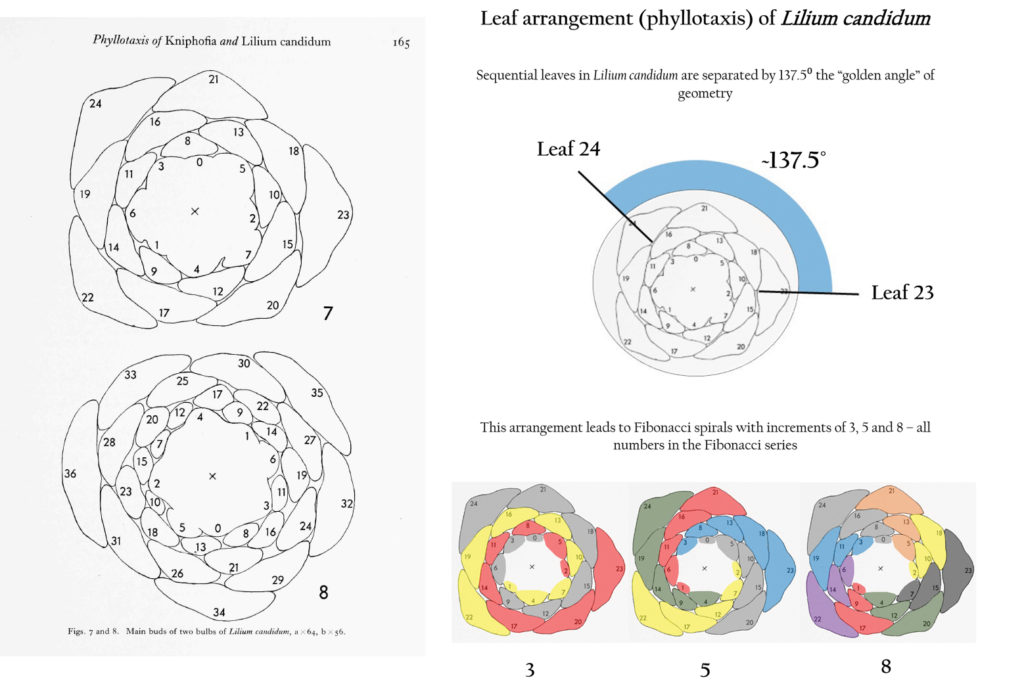

From: Snow, R. “Phyllotaxis of Kniphofia and Lilium candidum.” New Phytologist 57.2 (1958): 160-167. Courtesy of New Phytologist

Robin published his “Phyllotaxis of Kniphofia and Lilium candidum” in New Phytologist in 1958. In the paper Snow describes the arrangement of leaves (phyllotaxis) in bulbs of the Madonna lily – Lilium candidum. The figure shows two cross-sections of lily bulbs with the leaves labelled by their age; starting with the youngest leaf 0 at the centre and spiralling outwards. Snow noted that the angle between sequential leaves was approximately 137.5⁰ – the famous “golden angle” in geometry. The development of the leaves at this golden angle leads to the formation of both clockwise and anticlockwise Fibonacci spirals of leaves radiating out from the centre of the bulb.

Nearly half of all Robin Snow’s research papers from his career (30 of the 65) were published in New Phytologist – and these papers have together amassed over 1000 citations (Google Scholar, July 2018). A potential reason for the strong link between the Snows’ work and New Phytologist may be the links between Magdalen College and Sir Arthur Tansley – the founder of New Phytologist. Sir Arthur Tansley held the post of Sherardian Professor of Botany in Magdalen College, 1927-1937, and was therefore in Oxford during the time that Robin and Mary Snow were carrying out much of their ground-breaking work.